One certainly revolves around the cryptographic keys. The cryptographic security we’re using today that was originated in the Bitcoin blockchain truly comes from 20-plus years of cryptographic research. This wasn’t just invented overnight. The way of securing data in a distributed database through these keys is pretty unique and certainly uses cutting-edge securities. That’s number one.

Second, the idea that this is a distributed, a decentralized, database means that you don’t have some of these issues around a database breaking the single point of failure. What you’ve actually got is a system which is very robust. If one database fails, one copy fails, you’ve got that important redundancy across multiple nodes.

Third, the essence of blockchain is a chain of blocks of information together. When you have those blocks chained together, you’re creating a perfect audit history. You can go back through time and see a former state of the database. If you’re recording things like property titles, you can see a previous owner of the property and the current owner. You’ve got this perfect audit trail.

But perhaps the most important aspect here, and this is what’s getting people excited, is this idea of process integrity. And that is the database can only be updated when two things happen. One, the correct credentials are being applied, the private and public key together. But most importantly, those credentials are being verified by a majority of participants in the network. You can only update the database when the majority of independent computers check and verify those credentials that allow you to write to the database. You’re securing this against the idea of single point of failure and somebody working nefariously to try and corrupt the database. You have this democratization of the process of dating the database.

let us bring you in there. If you’re out at a dinner party, and you mention that you work in blockchain, what kind of responses do you get? And what do you hear are the misconceptions about it?

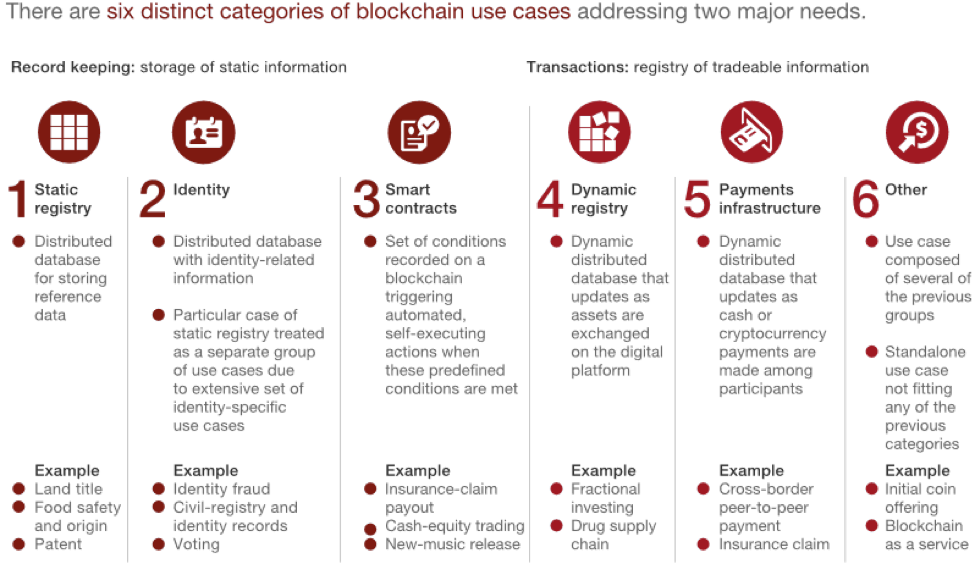

There are a lot of misconceptions [Exhibit 1]. A lot of people have heard of blockchain but really don’t understand quite what it is. You hear everything, from everybody thinking that blockchain is Bitcoin or vice versa through to “it’s a ‘truth’ machine unto itself.”

No, Bitcoin is an implementation of and leverages a blockchain in order to deliver a virtual currency. We often hear, “Is it better than traditional databases?” No, it’s not necessarily better than traditional databases. But blockchain is very effective in an environment where you need to have a decentralized way of working or you’re looking to take out a centralized entity—so in things like in trade finances.

That said, blockchain isn’t as efficient as traditional databases. It’s much hungrier in terms of energy use and in many cases has higher storage costs. By definition, it’s much more for specific use cases.

Is it immutable or tamper-proof? It is only as immutable and tamper-proof as the implementation itself. And, frankly, if you’re able to take over half the nodes in a blockchain network, it’s very difficult. But if you are, you can tamper with it because then you will be able to affect the consensus algorithm.

As far as it being a truth machine, well, the blockchain’s only as good as the information you put in it. So if you have a blockchain, and in the blockchain you’re keeping people’s driver’s license information or voting history, and you put in incorrect data, the data itself isn’t checked in any particular way. All that the blockchain itself does is ensure the integrity of the individuals making the transaction, ensuring that you have the right combination of a public and private key.

When we think about the original purpose, it was to reward the computers, the people doing the work, actually doing the verification process. And so a coin was important to provide monetary compensation for, in that case, the electricity being used to do the vast amounts of computation.

When we look to implementations of blockchain going forward, very rarely is it necessary to have a coin or some sort of reward. Instead the reward is access to data. If you think about a private blockchain, a closed-loop network of computers, all pursuing the same eventual goal, let’s say it’s in insurance or trade finance, then the reward is being part of that club, that private network. And, frankly, the reward is also being better able to share data and therefore generate better business processes.

One of the things that strikes us is that a lot of people are drawn to Bitcoin because you’re doing away with the central authority, the central banks in that case. Is disintermediation central to how a blockchain creates value?

Yes, absolutely, disintermediation is one of the ways it creates value, in that you don’t have a central authority. It does make things like trade finance much simpler because you don’t have intermediaries along the way. There’s a very good example: the UN, delivering some of their aid to Syria, has used a blockchain-based solution.

And by doing that, they’ve been able to actually authenticate individuals using biometric data and use that as a way to ensure that the aid give is given to the right people and it’s an equitable quantity.

This is a very clean way of taking out what would be traditionally money that would follow multiple steps and transaction costs to get to the end users. But there are also many other reasons why blockchain is effective. That is only one of multiple different sources of value.

The principle of disintermediation was a good one, in that the idea of democratization of data, streamlining processes, taking away the central agency power that could actually corrupt how data is being written and recorded permanently. When we looked at the practical applications today, and I’m sure we’ll talk more about that, the real irony in some ways is that in order to justify significant investment in this new technology, you actually need somebody to take a leading role very often.

You need someone to stand up and say, “I’m going to be the pioneer. I’m going to develop the platform. And perhaps I’ll bring industry partners in. But I’m doing this potentially because the business case says it gives me competitive advantage.”

The irony is, in those use cases where that makes more sense, the developers actually tend to be thinking in a more defensive way: “I already hold a central role in whatever ecosystem I’m playing in, and blockchain presents potentially a better solution.”

One example would be somebody who’s certifying the quality of a supply chain. Organic foods, non-GMO foods. In that case you might think of blockchain as providing the source of truth, the real gold-standard details of a supply chain. But the agencies who are developing it still want to hold that central role as being the authority on saying, “Yeah, this food is organic. And we can track it down the supply chain.” It’s a little bit of an irony or a contradiction there. Truly, it’s about disintermediation, but at the same time, those who are investing in the space think of it as a defensive play to strengthen their position in the center of an ecosystem.

It’s not all the purist view, which is, blockchain is solving industry problems, and this is the new world. There are three camps or categories of ways that companies are thinking about value.

One is that purist or academic value, which is, there are intrinsic properties of blockchain, which—this goes to the point about being a better mousetrap—really do solve industry problems. They provide a way of sharing data securely across multiple parties. Things like supply chain or trade finance would be absolutely perfect for that camp.

I do think there are a lot of folks who are saying, “Actually, maybe it’s not about the technology. But maybe there’s something around using blockchain as a banner to modernize an industry, to move an industry forward—and also to bring that industry closer together, to collaborate, to solve perennial problems—even if the eventual technology solution is not necessarily blockchain the way we think about, but it is much more around digitization and collaboration.” I think there are a lot of clients thinking in that space.

Then I think there’s, cynically, a third group, who are looking at blockchain purely for its reputational value and saying, “I want to prove to shareholders and the rest of the world how innovative we are. I’m going to start a proof of concept [POC] for things like employee rewards points,” a use case that in no way would benefit from blockchain. “We have reward systems that work perfectly well without it. But if I announce I’m doing a POC, I can attract some attention, whether it’s from investigators or shareholders or the like.”

When we look at the balance between those three, probably that middle group is the one where we’re seeing the most traction. We’re seeing blockchain as a banner to attract investment, to modernize an industry, agnostic potentially of the end solution, the technology being used.

In the last couple years in certain industries, including the finance industry, there’s a little bit of this disillusionment coming through. We’ve seen lots of investments, to your point, lots of POCs.

Yet we would encourage all players in industries who have been doing POCs to take learnings from those initial pilots. There are many industries that are still very manual based, very paper based. Take transaction banking. The cash-management, trade-finance components are still using technologies that, charitably, are 20 years old. There is momentum here. There is investment here to modernize an industry, even if those early POCs don’t appear to have borne fruit yet.

Surely another issue is that many of those 20-year-old technologies that you mention support quite profitable lines of business for financial institutions.

They do. It’s a very fair point. The best example I can think of is cross-border payments. Cross-border payments, again, have been using fairly old technology. Up until very recently, you may have taken three to five business days to complete a cross-border payment transaction in certain corridors. You might have paid 2 percent, 3 percent, up to 10 percent in fees and commissions along the way. And, frankly, in the middle of that transaction, for several days, your money disappears. It literally is invisible. For certain big, international money-transfer organizations, this has been a very profitable revenue stream. These are good margins. And these are margins shared out end-to-end across that payments value chain. The promise of same-day, seamless, low-cost, cross-border payments—instantaneous payments using blockchain—is one that truly is disruptive.

To be fair to the industry, the major players have looked at this technology, but there’s always going to be a bit of a defensive play. Now, what we’ve actually seen in cross-border payments is that perhaps the dominant messaging player here, SWIFT, has looked at various technologies and has driven modernization using its global payments initiative to improve the customer experience, to get to that same-day experience.

That is forcing the industry to modernize. And, naturally, those margins are coming down. So the evolution of this technology is driving improvements. But, certainly, we are still hearing resistance from certain business-unit leaders, as you’d expect, to this new innovation.

Let’s talk a little bit more about the potential use cases. How do you categorize them? One of the pieces of terminology I came across is static registry versus dynamic registry. Tell us a little bit more about the use cases and, in particular, about static versus dynamic.

When we did our research and looked across industries, we found fundamentally six different categories of business applications [Exhibit 2].